Hazard Controls for COVID-19

Assess Workplace Hazards

COVID-19 has been recognized as a workplace hazard. No one knows your operation or processes better than you do. Whether you are a farmer, FLC, or farm supervisor, just as you would consider the potential for safety hazards when introducing new equipment or processes into your operation, you should utilize a similar approach now with COVID-19.

Steps to take when conducting your COVID-19 assessment:

- Understand the hazard

- In the case of COVID-19, the hazard is the spread of the virus through respiratory droplets from person to person and on surfaces. These are the two areas to address.

- Systematically inspect your workplace: Identify where workers may encounter the hazard and consider the following questions.

- Person-to-person contact:

- Where do people typically come into close contact at your worksite?

- How do workers and non-employees (e.g. deliveries) enter your worksite?

- Where and how do workers clock-in? Is there sufficient space? Are there dividers between clocks?

- Where and how are meetings and trainings held? Can you adjust the size of the group to allow for distancing?

- Where do workers take breaks? How can you facilitate the recommended 6 feet of physical distance?

- Contact with infected surfaces:

- What tools and equipment are shared? How about chairs, water jugs, doorknobs?

- Will you need to make changes to your cleaning and disinfection procedures? How often will these areas need to be disinfected?

- Person-to-person contact:

- Consider frequency of prevention activities: As you assess areas of risk, consider whether any changes you implement will be a one-time change or if they will need to be ongoing (e.g. daily, like cleaning).

- Implement your control plan: After you have assessed areas of risk, you can create and then implement your control plan.

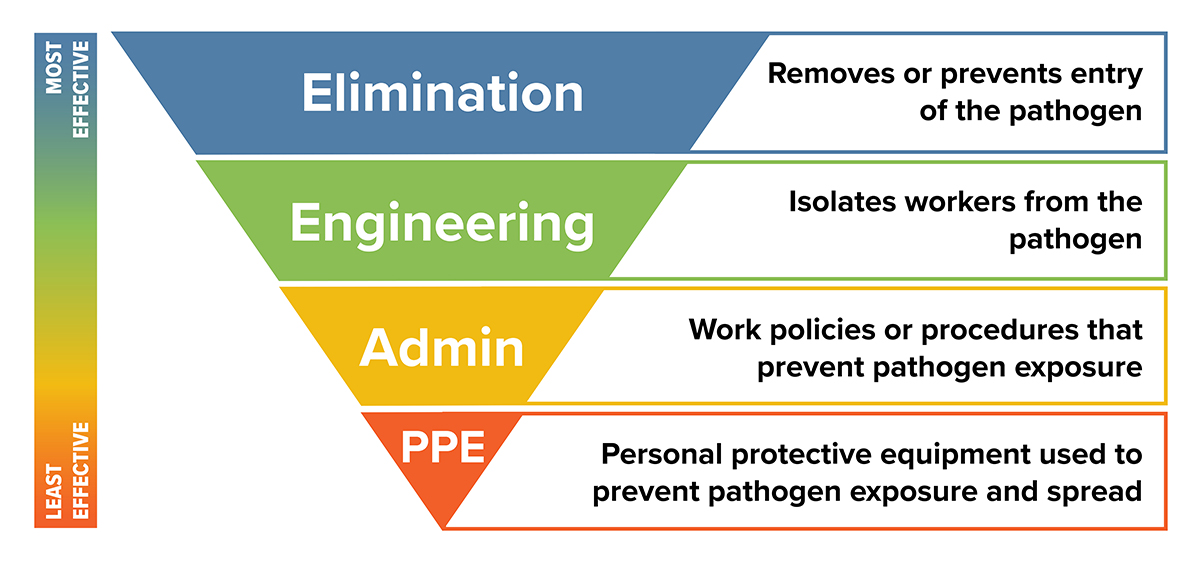

Hierarchy of Controls

The hierarchy of controls is a framework to identify strategies to reduce workplace hazards. The vertical arrow on the left indicates that some strategies are more effective than others and should be prioritized. Unfortunately, for an essential industry like agriculture, where in-person work is required, elimination of the hazard (e.g. the virus) is not possible at this point, unless the operation closes.

Engineering Controls

After elimination, engineering controls are the most effective because they isolate the worker from the hazard. Examples include: installing plastic shields or barriers between workers; using plastic “curtains” between workers following a combine; rearranging chairs or tables to ensure 6 feet of physical distance in break areas; and ventilation controls, such as the use of special filtration systems and removing personal fans.

Administrative Controls

Next in the hierarchy are administrative controls, including policies and procedures to prevent exposure. A lot of the controls that you are already implementing fall into this category, such as establishing and promoting leave policies, face covering use, physical distancing, cohorting workers, effective and ongoing training, alternating lunch breaks, the provision of accessible hand washing stations, and disinfection and hygiene procedures.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

Personal protective equipment is the least effective control method because it requires workers to use the PPE correctly and consistently and for the PPE to fit correctly. COVID-19 does not in itself dictate the use of new PPE in agricultural settings, but experts have identified the use of cloth face coverings as an effective way to reduce the spread of the virus. Technically, cloth face coverings are not considered PPE because they are primarily worn to protect others from the wearer.

It is important to note that Cal/OSHA now requires employers to provide cloth face coverings. This new requirement doesn’t exempt employers from their obligation to provide the appropriate level of PPE (e.g. respirators, coveralls, aprons, or gloves) for identified job tasks. Workers must also be trained on how to properly use and remove PPE.

Developing Your Control Plan

After you determine what actions you will take to control the hazard and develop your plan, pause and ask yourself how your plan aligns with the CDC and Cal/OSHA guidelines:

- Do you have a plan to regularly (e.g. daily, weekly) assess your workplace for the effectiveness of your control strategies? Will they need to change over the course of the season?

- Do you have prevention controls in place for all aspects of your operation (e.g. harvesters, irrigators, drivers, office staff)?

- Do you know what you will do if a worker experiences COVID-19 symptoms at work?

- Do you have a plan to regularly check for local, state, and federal updates related to COVID-19?

- Do your workers know how to find information about COVID-19, how it is being prevented at your worksite, and who to contact with questions?

- Do you have COVID-19 information for your workers in the appropriate languages and literacy levels?

Document and communicate your plan but know that hazard assessment is an ongoing process and will be most effective if you engage everyone in your operation. Consider asking for feedback about potential risks from workers during meetings. If your FLC, foreman, or supervisors are implementing COVID-19 prevention practices in the field, consider doing a walk-through with them to have a new set of eyes to identify potential areas of risk.

Consider using the Written Worksite Specific Plan from the California Department of Public Health and Cal/OSHA as a guide to create your plan.

Worker Trainings

Worker training should be conducted regularly, in a way that is easily understood by all workers. Remember, this is a new hazard that people are not yet used to dealing with. Frequent trainings and reminders are important. Also, remember not to delay other critical trainings (like heat illness prevention) due to the challenges of bringing people together.

This article is based on the Worker Occupational Safety and Health Training and Education Program (WOSHTEP) administered by the Commission on Health and Safety and Workers' Compensation in the California Department of Industrial Relations through interagency agreements with the Labor Occupational Health Program at the University of California, Berkeley; the Western Center for Agricultural Health and Safety at the University of California, Davis; and the Labor Occupational Safety and Health Program at the University of California, Los Angeles.